|

GC6F19K

PPHS Teacherage

PPHS TeacherageType: Traditional | Size: Regular  | Difficulty:

| Difficulty:  | Terrain:

| Terrain:  By: Pikes Peak Historical Society @ | Hide Date: 04/11/2016 | Status: Available Country: United States | State: Colorado Coordinates: N38° 56.895 W105° 17.670 | Last updated: 08/30/2019 | Fav points: 0

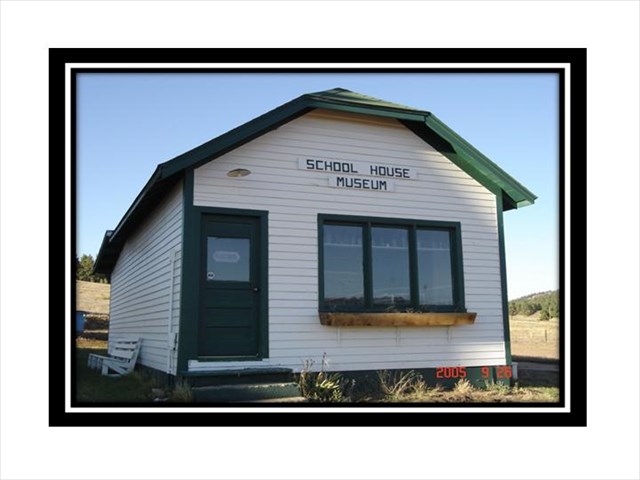

Part of a series sharing historical information about the Pikes Peak backcountry placed by the Pikes Peak Historical Society. An intact school complex that includes the original school house, teacherage, out houses and coal house. This museum is open annually for Florissant Heritage Days or to arrange for appointment at least 24 hours in advance contact PikesPeakHSMuseum.org or call 719-748-8259. Admission is free.

With the addition to the school in 1889, Florissant loosened its purse strings for an embellishment—a large bell tower with a Queen Ann-style turret. This school bell was essential to the life of the Florissant community. It not only called the children to school, but also rang in case of any emergency, especially fire. Somewhere around this same time, the school district also added a shack for storing coal out behind the schoolhouse. This shack was later used in the early 1900s as a cook shack when hot meals were served to the children. A teacher’s residence was also added in the early 1900s. All of these buildings, including the school, were placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1991. In 1960, the Florissant School was shut down and the teacherage was moved to Woodland Park. Then, in 1993, the Florissant Heritage Foundation (Pikes Peak Historical Society) was awarded a grant to restore the old school. The teacherage was returned to its original location, and restored with donations and is now the Florissant Schoolhouse Museum. (In 2001, The Florissant Heritage Foundation changed its name to the Pikes Peak Historical Society.)]

Pikes Peak is a sacred mountain to the Ute People. Not only do their creation legends refer to Tava, but archaeological and cultural evidence also document it as central to Ute spiritual and ceremonial use. Amazonite crystals were gathered by their poowagut (holy men and women) from Crystal Peak and taken to Pikes Peak to be blessed in ceremony. Each summer, a Sundance Ceremony was held on Pikes Peak. Even today, the Ute People still follow this tradition. UTE TRAIL TO DENVER On the east side of the School House Museum is County Road #3, which was originally a Ute lodge-pole trail leading to Crystal Peak, and then on to Denver. A special Ute agency was established in Denver to accommodate the Northern Utes.

Add cache to watch list Log your visit Picture Gallery

Lift wire handle.

GC2T1ZV Burn 1st View (16.04 kms NE) GC2T209 Butte View (17.81 kms NE) GC26MWG Sport's Beaver Creek Cache (23.21 kms SE) GC2T203 No pines (25.64 kms N) GC5R8JR The Bearing Tree (36.06 kms NE) |

Driving Directions

10 Logs:

|

Florissant’s one-room log school built by early settlers somewhere near the Florissant Pioneer Cemetery in the early 1870s could not accommodate all of the new students after the Colorado Midland Railroad arrived in town. A building fund was begun in 1886, and Frank Castello sold an acre of land to School District Number 13 for one dollar.

Florissant’s one-room log school built by early settlers somewhere near the Florissant Pioneer Cemetery in the early 1870s could not accommodate all of the new students after the Colorado Midland Railroad arrived in town. A building fund was begun in 1886, and Frank Castello sold an acre of land to School District Number 13 for one dollar. Florissant’s little white school was built with its entryway facing south, toward the Ute Pass Wagon Road and West Twin Creek. This little room was lined with brass coat hooks on one wall and wooden shelves on the opposite wall. These shelves were used by students to store their lunch buckets, made from a half-gallon size lard or syrup pail. Most lunches consisted of a jelly sandwich, or perhaps a fried egg sandwich, placed on thick slices of homemade bread or biscuits. It wasn’t unusual to find that the bread had frozen while sitting in the anteroom, and had to be toasted on the top of the pot-bellied stove. These sandwiches were washed down by cold spring water, brought up from the creek and shared from a common dipper.

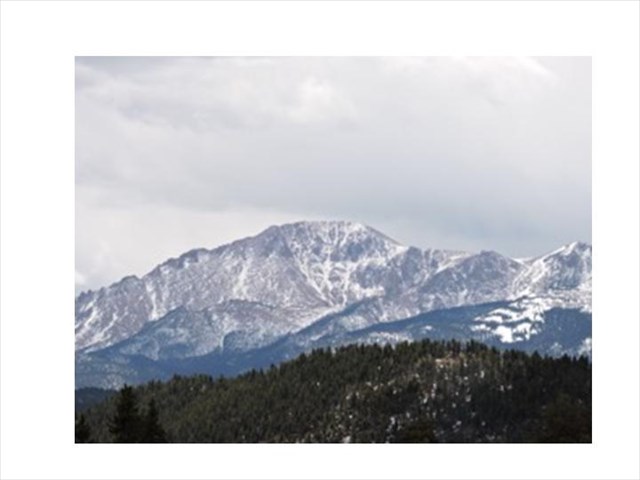

Florissant’s little white school was built with its entryway facing south, toward the Ute Pass Wagon Road and West Twin Creek. This little room was lined with brass coat hooks on one wall and wooden shelves on the opposite wall. These shelves were used by students to store their lunch buckets, made from a half-gallon size lard or syrup pail. Most lunches consisted of a jelly sandwich, or perhaps a fried egg sandwich, placed on thick slices of homemade bread or biscuits. It wasn’t unusual to find that the bread had frozen while sitting in the anteroom, and had to be toasted on the top of the pot-bellied stove. These sandwiches were washed down by cold spring water, brought up from the creek and shared from a common dipper. TAVA - Rising majestically above the Florissant Valley in the east is TAVA, the Ute name for Pikes Peak, which means “Sun” in their Uto-Aztecan language. The Spanish were the first Europeans to document Pikes Peak, and their chronicles refer to it as “El Capitan” or “Chief.” This naming probably came from Ute informants. However, in the Ute dialect of the Aztec language, the words for Sun and Chief are interchangeable, therefore they found no discrepancy between these two names. The ancestral Ute who first frequented the Pikes Peak region called themselves the “Tabeguache.” When John Wesley Powell lived among the Utes in 1868-69, they taught him that in their culture they identified themselves as “belonging to the earth” at specific places. Therefore, the band name “Tabeguache” means the “People of Sun Mountain.”

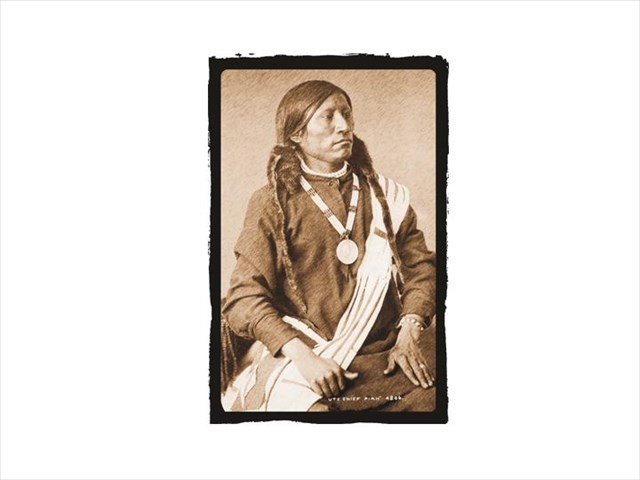

TAVA - Rising majestically above the Florissant Valley in the east is TAVA, the Ute name for Pikes Peak, which means “Sun” in their Uto-Aztecan language. The Spanish were the first Europeans to document Pikes Peak, and their chronicles refer to it as “El Capitan” or “Chief.” This naming probably came from Ute informants. However, in the Ute dialect of the Aztec language, the words for Sun and Chief are interchangeable, therefore they found no discrepancy between these two names. The ancestral Ute who first frequented the Pikes Peak region called themselves the “Tabeguache.” When John Wesley Powell lived among the Utes in 1868-69, they taught him that in their culture they identified themselves as “belonging to the earth” at specific places. Therefore, the band name “Tabeguache” means the “People of Sun Mountain.” Chief Piah was the traditional chief of these “Denver” Utes. He was the brother of Chipeta, and after his wife died, she and her husband Ouray adopted all of his children. Ouray was the traditional chief of the Tabeguache Band of Ute, and the U.S. Government named him as chief of all the Ute. This was a violation of Ute tradition, but made it easier for the government to negotiate treaties. Piah frequently visited Ouray’s camp to see his sister and his children. Florissant’s main street, now Highway 24, was originally named “Piah Street.”

Chief Piah was the traditional chief of these “Denver” Utes. He was the brother of Chipeta, and after his wife died, she and her husband Ouray adopted all of his children. Ouray was the traditional chief of the Tabeguache Band of Ute, and the U.S. Government named him as chief of all the Ute. This was a violation of Ute tradition, but made it easier for the government to negotiate treaties. Piah frequently visited Ouray’s camp to see his sister and his children. Florissant’s main street, now Highway 24, was originally named “Piah Street.”